Have you wondered where the water goes after you flush the toilet, wash clothes, or use kitchen and bathroom sinks?

Each year, Clackamas Water Environment Services (WES) treats and cleans more than seven billion gallons of wastewater from homes and businesses in northern Clackamas County and returns it to our rivers. That’s almost enough for a gallon of water for every person on the planet.

While serving the wastewater treatment needs of nearly 200,000 customers, WES protects public health by preventing the spread of potentially deadly diseases that can come from dirty water, as well as protecting our shared environment.

WES’ largest two treatment facilities are the Tri-City Water Resource Recovery Facility, which cleans a daily average of 10 million gallons, and the Kellogg Creek facility, which cleans nearly seven million gallons a day.

How does WES do this? It’s a combination of gravity, chemistry, and much more.

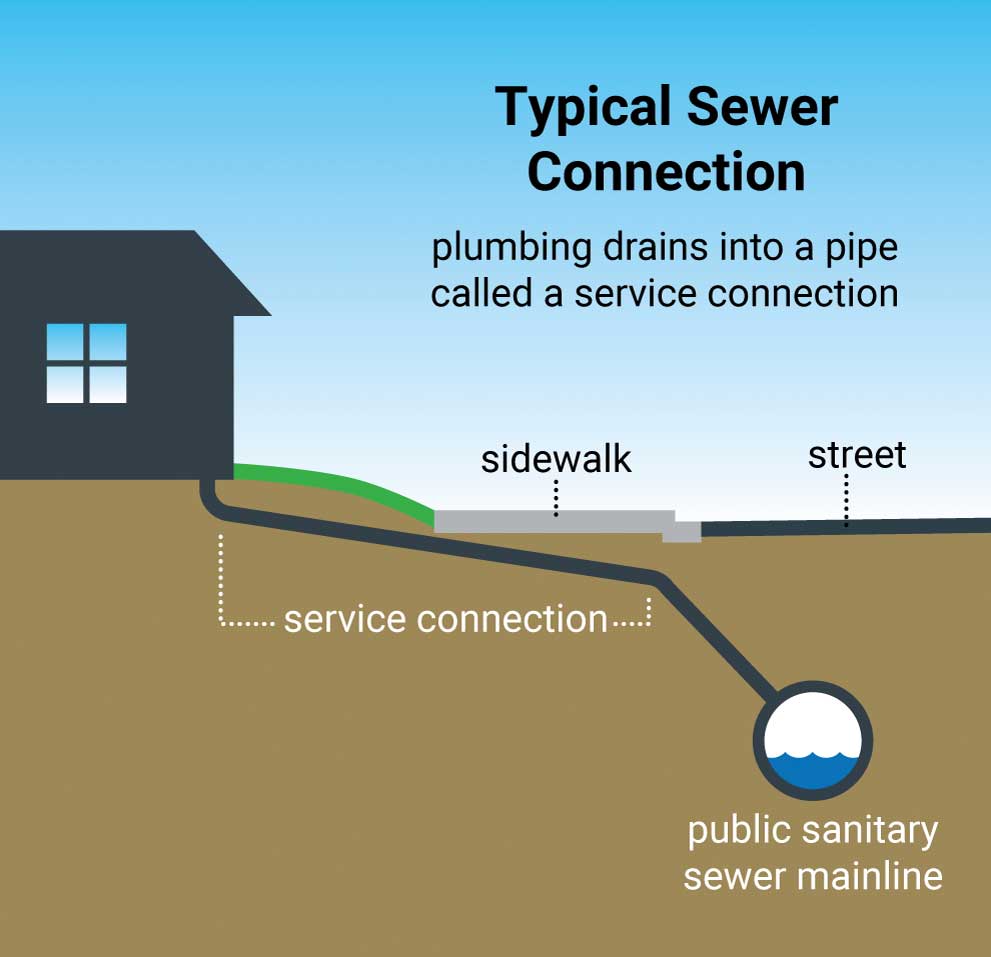

As it leaves your house, wastewater travels in a pipe called a service connection, and then into a main sanitary sewer line beneath the street. That’s when gravity kicks in, helping deliver the fl ow to one of WES’ fi ve treatment facilities. WES owns and maintains more than 360 miles of pipes to carry the water.

Pumping stations lift the wastewater over hills where needed.

Where it all happens

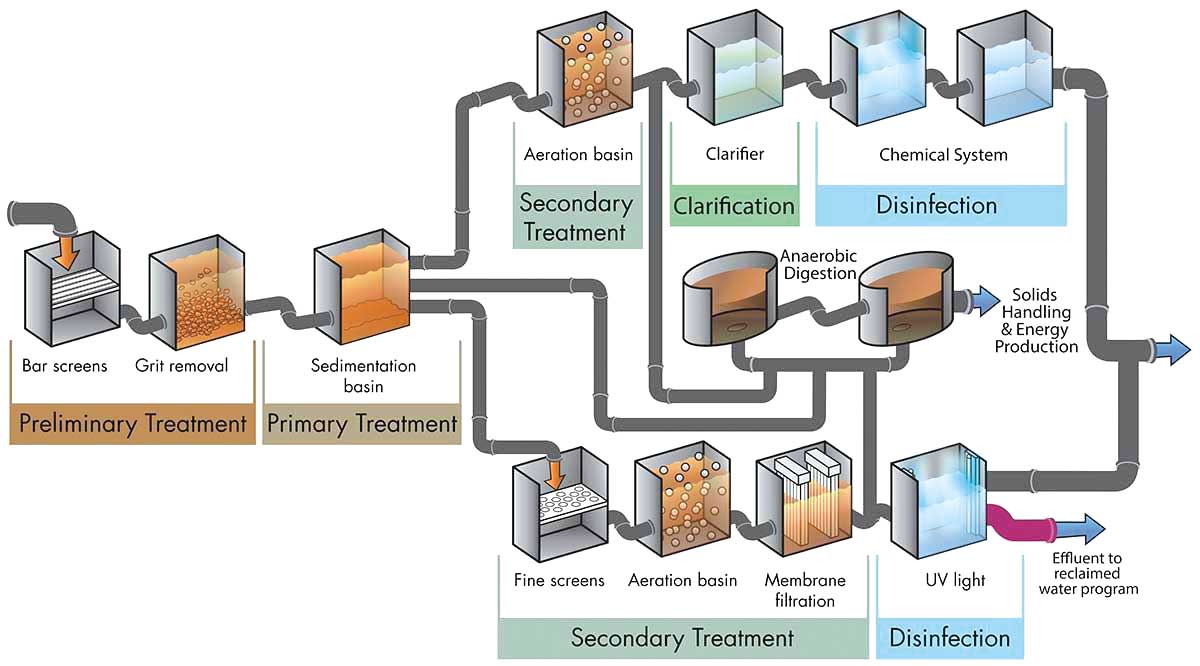

Once untreated wastewater arrives at a WES treatment facility, the first stop is bar screens, which remove the biggest solid objects like plastic, paper products, and rags.

Next in the grit chamber, the flow slows down to allow objects like rocks, sand, coffee grounds, and food waste particles to settle to the bottom.

After grit removal, the water goes to primary sedimentation basins, where remaining solid objects sink to the bottom as sludge, or rise to the surface as scum.

The scum and sludge are removed and sent to the digesters (large tanks), where they are treated with anaerobic bacteria. Anaerobic means that no oxygen is involved. The digesters convert sludge to biosolids that are used as soil conditioner and methane, which is converted to electricity used to provide power for the Tri-City facility.

Biological treatment 101

The Tri-City facility uses two biological treatments: a conventional activated sludge process and a Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) process.

Conventionally treated water is sent to aeration basin tanks where pumped-in air promotes the growth of bacteria. Oxygen-loving microbes break down organic waste into carbon dioxide and water. The water is then disinfected with bleach.

Water treated in the MBR flows through hollow-fiber membranes to remove contaminants, and then to the ultraviolet disinfection building, where it is disinfected by powerful UV lights.

Natural air freshener

There are mechanisms for minimizing unpleasant odors. Air from some processes is sent either to a carbon tower or through a biological odor control tower, where microbes neutralize odor-causing gasses, providing a natural alternative to chemicals.

Final leg of the journey

After being biologically treated and disinfected, conventionally treated water goes to secondary clarifiers, which are big tanks that capture and recycle most microbes to the aeration basin. Excess microbes are sent to the digesters.

Treated water from both the MBR and conventional processes is sent downstream of the UV building, where the water is analyzed for compliance with state and federal safety guidelines.

Finally, the cleaned water, called “effluent,” is then returned to the Willamette River, completing the journey from your home to the river.

Translate

Translate